Preface

Sensing that my days on this earth are drawing to a close, it felt appropriate to give a brief summary of my life story; to explain something of the forces and influences that have shaped my music, and to demonstrate the principal features of my compositional style through reference to each of my major works. My words are intended for informed and inquisitive music-lovers, to provide a readable introduction to my music, to give a sense of the range of my creative output, and, hopefully, to stimulate greater interest in my compositional oeuvre.

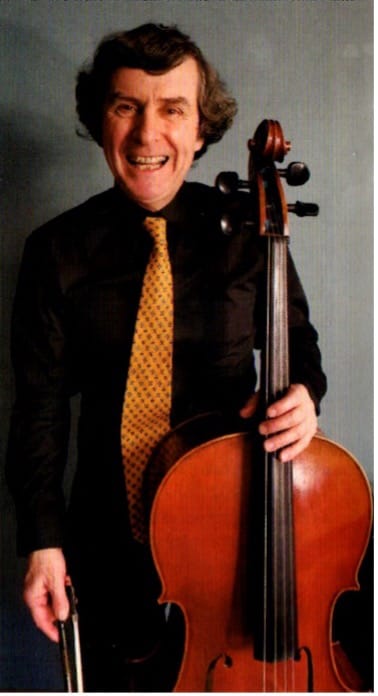

Robin Stevens, Baguley, Manchester, July, 2025.

I – Childhood and Undergraduate Years

I was born in Newport in the south-east corner of Wales on 30th August, 1958. My father, Robert Desmond Stevens, came from very humble beginnings in Longsight, Manchester to become, in his early thirties, the principal of an engineering college in the Midlands. Robert had a beautiful baritone voice, and a genuine love of Classical Music, but his great passion in life was rock climbing and mountaineering, and throughout my childhood, half of each school holiday was spent with him in the hills, whilst camping or staying at Youth Hostels.

My mother, whose professional name was Gillian Butterworth, grew up in Newport in a rather conventional middle-class home. Her father was a dentist, who struggled to comprehend the musical leanings of his highly intelligent daughter. Mother, as well as being an able pianist, was also skilled at languages: never a technical virtuoso at the keyboard, she was happiest training and accompanying singers in the performance of French and German song; instinctively she understood the particular sensitivities and vulnerabilities of vocal performers. Playing chamber music was another great love.

My childhood was unsettled. My parent’s marriage, never very stable, was dissolved when I was five years old. I then lived with my mother, and my sister, Louise, who was two years younger than me, but I am grateful that I managed to maintain regular contact with my father. Before I reached senior school I had lived in the Isle of Man, in Devon (on the outskirts of Plymouth), and Stevenage in Hertfordshire. When I was eight we moved to Winchester in Hampshire. Mother – nothing if not resourceful – was not the type of woman to live off the state (harder, anyway, in the early 1960’s than today), and made ends meet as a single parent by holding down a lecturing job, and taking lodgers in our terrace house. Three years later my mother married the Welsh landscape artist, John Elwyn, and materially at least, life became more comfortable.

Music was a steady undercurrent to my upbringing. Even as a young child, I would sing myself to sleep by recalling piano pieces my mother would have played in the home. Sometimes, apparently, I would surprise her with a piece she hadn’t played for quite a while – my ‘ear’ was good, even then!

I started playing cello when I was eight, and I owe a lot to Dorothy Milner, my first cello teacher; boundlessly enthusiastic and encouraging, Dorothy brought a passion and commitment to music-making which has remained with me throughout my life. Temperamentally, the cello ‘fits’ who I am – intense and soulful, with a dash of flamboyance. I also owe a considerable debt to my first piano teacher, Brian Eastop, who was endlessly patient with me through my difficult early teenage years, when I practised very little; his gentle perseverance paid off, and by the time I left home, Brian had the satisfaction of knowing that he had helped me acquire a basic keyboard grounding that brought me much pleasure, and a skill-set I could call upon as a composer, and later as a school music teacher.

A pivotal moment in my musical development happened in the Autumn of 1970. The French cellist, Paul Tortelier, was then at the height of his fame, and BBC2 aired a master-class, given by Tortelier, on the first of Beethoven’s five Cello Sonatas, to celebrate the bi-centenary of Beethoven’s birth. This piece must be one of the least-known of Beethoven’s major works, but, watching and listening in our living-room in front of our black-and-white telly, I was transfixed. Arguably, in that one evening, my future course as a composer was set. In the next few days I began scribbling down cello and piano music very obviously imitating the German master, and over the next four years, until I left home at just sixteen, I produced a steady stream of highly derivative – but, in their own unambitious terms, reasonably competent, chamber compositions.

I loathed the local boys’ Grammar School which I attended from 1969-1974, and left school as soon as I could, to do a two-year preparatory music course at the now-defunct Dartington College of Arts near Totnes, Devon. Dartington was good news for me: I revelled in its freedom, after the (for me, at least) harsh and unfriendly environment of senior school, and musically I flourished, gaining a solid, all-round musical education, and managing, at the age of sixteen, to give a complete performance of the Elgar Cello Concerto with the College Orchestra. At Dartington I also played plenty of chamber music, a particular highlight being a concert performance of Mozart’s G minor String Quintet. I owe a special debt to Benedict van Weede, 2nd viola player in that quintet, who invited me to church on my first Sunday away from home: that day I heard the gospel clearly proclaimed, and became a Christian, a major life commitment which has held firm through the inevitable ups and downs of the intervening half a century.

At eighteen my musical studies continued in Manchester as I undertook a course combining a Music degree at the University with an undergraduate course at the Royal Northern College of Music, the latter as a first study cellist. I did not enjoy music college. I did, however, greatly enjoy the University Music Department, which in the late 1970’s was a happy and supportive place, and in my third year I was conductor of the University Chamber Choir. I continued to revel in the pastiche exercises (imitating, for example, a Haydn String Quartet or a Schubert song, or vocal counterpoint by Palestrina) which then formed the bedrock of an academic course, and even now I am grateful for the solid grounding in traditional compositional skills which I gained in those years: true, I was rather slow as a composer to break free from the anachronistic constraints these exercises placed upon my creative imagination, but in the longer term the protracted gestation period over which my individual compositional style emerged was, I believe, to my advantage.

In my undergraduate years, a couple of influences stand out. I conducted a student ensemble in Vaughan Williams’ choral masterpiece, Flos Campi, and this piece made a huge impression on me: most particularly, the bitonal opening (solo viola pitted against the oboe), and the pastoral tranquillity of its glorious closing pages, sincerely and unapologetically tonal and melodic. The modal inflections of Vaughan Williams and English folksong remain an important strand in my music. Contrastingly, in my early 20’s my own stuttering attempts at musical originality were rather bogged down by rhythmic squareness and a suffocating harmonic complexity of the kind that abounded in Vienna around the turn of the 20th century. My harmony tutor, Geoffrey Poole, set me on a new, more fruitful path, by suggesting I ‘take a good look at plainchant’. This was excellent advice! The rhythmic freedom of plainchant, the absence of regular barlines, and the revelling in melody for its own sake, were a liberation to me, and partly as a consequence, recitative-like, quasi-improvisatory passages in ‘free’ rhythm occur with great regularity in all my major compositions.

II – Early Period

In 1980, believing that becoming a music lecturer might be a realistic ambition for me, I undertook two years of postgraduate study at Birmingham University, under the South African composer, John Joubert. My rather conservative MA thesis was ‘Cyclic Form in Romantic Instrumental Music from Beethoven to Elgar’ – I was still a traditionalist in many ways, and never was (nor ever have been since) any sort of an iconoclast or musical rebel. John Joubert was a lovely, humble man, who encouraged me creatively, and whilst writing my thesis I decided to have a decent stab at becoming a serious composer. The result was my first major composition, a four-movement String Quintet, imbibed with a veritable host of early 20th century influences – Elgar, Walton, Stravinsky, Vaughan Williams, and the like. As the American tourist said on seeing Hamlet for the first time, ”Gee, I didn’t realise it was so full of quotations!”. Yes, the stylistic derivations (and even some thematic borrowings) are easy to spot, but, particularly in the revised version of 2018, the Quintet stands up on its own terms, and I still view it with great affection. Perhaps the best moment in the Quintet (John Joubert’s favourite moment, anyway!) is the transition from the end of the scherzo into the start of the slow movement: this is an instance of my adopting a procedure from an earlier composer’s work – in this case, the parallel place in Elgar’s First Symphony, where the main scherzo theme is radically slowed down to lead directly into the ensuing Adagio, the pitches of the scherzo theme being rhythmically transformed to become the opening melody of the slow movement itself.

Mercifully, on completing my MA at Birmingham, no offer of a lectureship was forthcoming – realistically, I am not a natural academic! Instead I obtained a post at St. Paul’s Anglican Church in York, where I worked for five years as Music Director and Pastoral Worker. Over this period I wrote a considerable quantity of worship music, which very gratifyingly became an integral part of the worshipping life of this solid, socially mixed Christian community. Some of this music has endured: the majority, as is normally the way with worship material, has not, but my work at St. Paul’s enabled me to keep the ‘common touch’, and made me wary of ivory tower elitism: yes, there is a place for complexity in contemporary composition, but sometimes we composers are too clever by half, and perfectly capable of unconsciously employing unnecessary complexity as a smokescreen for a paucity of musical invention and inspiration.

Towards the end of my time in York, pastoral activities took a back-seat, and I started to focus again on instrumental composition. Three substantial pieces emerged between 1985 and 1987: the Fantasy Sonata for violin and piano; the Sonata Tempesta, again for violin and piano; and the Sonata for Unaccompanied Cello. The Fantasy Sonatais a sixteen-minute, single-movement composition based entirely on the octatonic scale, rising by alternating semitones and tones (that is, B-C-D-E flat-F-F sharp-G sharp-A-B): very unusually for such a substantial piece, the scale is never transposed, so the pitches C sharp, E, G and B flat are completely absent from the whole piece. This gives the composition a highly individual character, and whilst such a strict compositional parameter could easily have cramped my creative imagination, it actually did just the reverse, stimulating me to explore new melodic and (especially) harmonic dimensions. Stylistically the Fantasy Sonatamight be described as ‘Olivier Messiaen meets Ernest Bloch’, and there is a sense of Romantic sweep to the whole, most especially in the tumultuous closing bars. Structurally, the piece is divided into two halves, consisting of a Statement and a Varied Counter-Statement: the second half of the work is the first of many instances in my music of the telescoping of development and recapitulation to create a ‘continual variation’ approach to form.

The Sonata Tempesta for violin and piano, which followed hard on the heels of the Fantasy Sonata, is an expansive, four-movement composition, again in a Late-Romantic/early 20th century idiom. A turbulent opening movement, and a tense, dramatic scherzo, precede the heart of the work, the lyrical slow movement: in this Andante tranquillo I again employed a particular scale, Messiaen’s third mode of limited transposition – that is, a scale built upon two rising semitones and a rising tone (the notes A sharp-B- C- D- D sharp E- F sharp-G-G sharp-A sharp). Interestingly, over thirty years later, when I came to revise this movement in preparation for a recording, I sensed that, come the coda, the music needed an extra expressive dimension, so I relaxed my strict adherence to Messiaen’s third mode, and the fresh harmonic regions I was then free to employ gave the coda a sense of culmination it had formerly lacked. The finale of Sonata Tempesta begins with a disarmingly chirpy rondo them, but soon the turbulence of the opening movement resurfaces: in the end, however, the work drives to an unambiguously triumphant conclusion. Not a smidgeon of Post-Modern irony to be found here! Whilst of course art can legitimately explore ambiguity and uncertainty, yet joy, truth and goodness are genuinely present in our world, and where art neglects or denies them, it will rarely touch and nurture the soul.

With the Sonata for Unaccompanied Cello, another substantial, four-movement composition, my Early Period (to be a touch portentous) came to an end. Unsurprisingly, I have written a large quantity of music for my main instrument, the cello. Whilst I am a competent, rather than outstanding, cellist, writing for my instrument is easy in that I know immediately what will be playable and sound well, and can utilise unorthodox hand shapes and tonal registers which would be hard to imagine if one was not so familiar with the geography of the instrument. Particularly in writing unaccompanied cello pieces, I feel like a potter at the wheel, clay and water in hand: the physicality of the cello inspires flights of compositional fancy which would be closed to me if I continued writing (as usual), at a piano. The Unaccompanied Cello Sonata begins with a ‘motto’ theme, which recurs at the start of the slow movement, and again at the climax of the finale. The piece is in D minor/major, making much use of the sonorities of the open D and A strings of the instrument, and the resultant harmonics. The slow movement is an unapologetic tribute to the English Pastoral Tradition – six minutes of unbroken melody. The finale, by contrast, is an enormous, breathless, moto perpetuo, climaxing in a triumphant return of the ‘motto’ theme in the upper reaches of the cello, and a helter-skelter downward cascade finishing in the depths on an emphatic, unison D.

I moved on from York in 1987 at the age of twenty-nine to undertake a one-year PGCE qualification at Bretton College in West Yorkshire to become a Secondary School Music Teacher. My fellow students on this course were a talented bunch of musicians, from a refreshingly wide variety of musical backgrounds (jazz, brass bands, Latin American percussion, Classical orchestral players, etc.), and we were rooting for one another in the bear-pit that is secondary school education. The actual teaching lectures were hopeless – full of abstract educational theory, and of no practical use in the classroom. To be fair, however, when lecturers observed me actually teaching, their input was helpful. During my teacher training year I was meant to observe qualified teachers actually giving class music lessons; significantly, this hardly ever happened, which did not inspire me with confidence in the general level of class music teaching in Secondary Schools in the early 1980s.

I taught Music in a Comprehensive School in Halifax, West Yorkshire, for three years, and I would say that for my first year (when I temporarily, and quite deliberately, avoided composition entirely) I was a decent teacher. I could be inspirational and wackily different for those pupils secure and open-minded enough to receive what I had to give. But I had two main difficulties as a schoolteacher: firstly, I didn’t learn to pace myself, and in the end my health gave way; and secondly, there was in me a deep need to compose, and holding down a full-time teaching job whilst attempting to take creativity seriously, was, for me at least, an unrealistic goal. In the autumn of 1990, after a prolonged bout of influenza, I contracted post-viral fatigue, which kept me out of full-time employment for the next seventeen years. Throughout this difficult period, I did a little private instrumental teaching, but it was only on recovering my health in 2007 that I was able to embark on another large-scale composition.

III – Middle Period (1990-2013)

The years 1990-2007 were not entirely barren creatively, however. Major works were beyond me, but I could experiment with miniatures – mainly unaccompanied cello pieces, piano solos, and cello and piano duets. As a composer I find writing shorter pieces can be liberating: one can take risks and be daring, knowing that if a piece is not a success, it represents a few wasted days at worst – and a ‘waste’ one can still learn from: whereas, at best, unimagined creative avenues can open up, through the freedom of being willing to try something radically new.

Throughout my years of illness, slightly more substantial pieces did occasionally appear. Reconciliation? for solo piano (1998), is especially significant in being the first of my compositions where bi-tonality played an important role, and also the first time where a chorale appeared in my music. The Three Character Pieces for cello and piano, written in 2004, mark a move towards a more concentrated and intense style. In the first piece, Thunder in the Soul, the two instruments cut across one another with visceral, dramatic gestures: there are two brief lyrical episodes, but there is a new Expressionist intensity and concision in a determinedly dissonant, atonal idiom. Wistful Chorale weaves complex variations on a seven-phrase theme, a powerfully introspective lament. And the final piece, A Short Ride in a Dangerous Machine, pushes harmonic density to the limits in an exhilarating moto perpetuo.

In 2003 my father died, and I sensed, as I attended his funeral, that my days in Halifax were numbered: I needed to move on before life passed me by. This medium-sized, post-industrial town has much to commend it, but culturally and musically I was out on a limb, and, in the summer of 2004 I moved to Manchester, into a flat six miles south of the city centre, on the edge of Wythenshawe Park – a good move, and, twenty years on, I am still happy and proud to call this ethnically diverse neighbourhood home. My first Mancunian composition was Say Yes To Life, for violin and piano. In this five-minute piece, the harmonic complexity of the Three Character Pieces remains, but it is set against soaring melodic lines in the violin, and the work recalls Charles Ives in its combination of widely-spaced major triads in the bass, and glittering dissonances in the upper reaches of the piano.

In 2007 I finally got through my extended bout of post-viral fatigue. That summer, a couple of friends independently suggested that I undertake a PhD in Composition, and within a few weeks I had begun a six-year course of part-time postgraduate study, back at Manchester University. Having spent a decade and a half in enforced exile from large-scale composition, my deliberate intention as I began my PhD was to explore how to create expansive musical structures in a genuinely contemporary musical idiom. Thankfully, the PhD course at Manchester centred on actually writing music, rather than theorising about music, so, whilst supporting myself as a home tutor to Year 6 pupils (mostly Maths and English, rather than Music), and newly energised, I embarked upon the six big compositions that would form the creative substance of my PhD portfolio.

My supervisor for the first half of my PhD was the composer, Philip Grange, from whom I learnt a good deal. Phil was old school – irascible, rather confrontational, but with a twinkle in his eye and a lovely sense of humour. Most of the time our working relationship was fruitful, though unfortunately after three years we fell out, but I am particularly grateful that in my first year of postgraduate study Phil allowed me to join his study group, looking at some of the landmarks of mid-20th century Classical Music. My steepest learning curve came as I led the group study on Elliot Carter’s formidable String Quartet No.1. I had, and still do have, huge reservations about this piece: I feel it is at times complex simply for the sake of complexity, running with technical concepts as ends in themselves, rather than in order to fulfil a worthwhile expressive purpose. That said, its best moments are impressive indeed, and intellectually I found Carter’s compositional processes immensely stimulating, despite the overall impact of the piece being, to my mind, turgid and impossibly dense. The fruits of this study were my own String Quartet No.1 (2008), an ambitious single-movement work lasting a full half-hour. In this piece, robust, energetic counterpoint, rather than harmonic sophistication, propels the musical argument. From Carter I adopted complex cross-rhythms, simultaneously setting two (or more) versions of the same theme against itself in metrical canons, in rhythmic ratios such as seven against four, and five against three. I also ‘stole’ from Carter the simple but effective device of playing a loud, staccato theme against a quiet, sustained cushion of sound – so that the music seems to inhabit two contradictory expressive worlds at one. In the coda I resort to a further Carterism – dispensing entirely with one musical element to emphasise others: in this instance, dispensing with harmony in an extended, rapid unison passage (actually just as much a ‘crib’ from the finale of Chopin’s ‘Funeral March’ Piano Sonata), so that when harmony again kicks in for the final few bars, its impact is the more emphatic.

My String Quartet No.1 represents the high watermark (or low-point, depending on your aesthetic preference!) of my relationship to Modernism, and for some listeners it may therefore represent my most uncompromising, and consequently most satisfying, single composition. In concert performance its extreme, sustained difficulty renders it virtually unplayable, though in 2019 the Behn String Quartet made a very fine recorded version. In retrospect, it is a piece I am very proud of, especially in its contrapuntal intricacies, though its harsh, uncompromising sound-world is not a place I would wish to revisit too often…

As part of my postgraduate training as a composer, I wanted to extend my technical range by tackling traditionally ‘difficult’ instruments to write for, so my next major piece featured the Classical Guitar. The Fantasy Trio for Flute (doubling piccolo), Classical Guitar and Cello(2009)is another single-movement work, this time of fifteen minutes’ duration. I found the unique sonic potentialities of this unusual grouping of instruments inspiring, and the scarcity of repertoire for this instrumental trio is a source of regret: the guitar’s lightness of touch enables the flute and cello always to be heard, even in their more subdued lower registers, and the combination of plucked guitar strings and bowed cello strings is especially felicitous. I have already mentioned that the principle of ‘continual variation’ – as opposed to straightforward repetition or recapitulation – is a central feature of my style. The Fantasy Trioopens with an actual theme and variations, each new variation being prefaced by a brief, solo recitative (providing effective contrast to the predominantly three-instrument texture). In the faster, central Fantasia section, flute (or piccolo) and cello frequently play jagged melodic lines in rhythmic unison, against complex broken chords in the guitar: a particular sonic effect is the use of artificial harmonics in the cello in combination with high flute notes, giving the aural illusion of a flute duet (or flute trio, if the cello is double-stopping). This emphatically atonal, and decidedly serious piece ends humorously with a reversion, in the final two bars, to a straightforward C major triad – prepared, a quarter of an hour before, by the rising tenth, C to E, in the opening phrase of the entire work.

Continuing my quest to embrace ‘difficult’ instruments, I gave the harp an important role in my next composition, the Romantic Fantasy for Flute (doubling Piccolo), B flat Clarinet, String Quartet and Harp (2010). The forces employed for this composition are the same as for Ravel’s well-known Introduction and Allegro, though the piccolo does not feature in Ravel’s work, and, for better or worse, my composition is arguably the weightier of the two pieces. This 23-minute, single-movement work is written in the symmetrical ‘arch’ form pioneered by Bartok, but also prefigured in my earlier Fantasy Sonatafor violin and piano (see above). Like the Fantasy Sonata, the second half of my Romantic Fantasyis a varied re-working of the material of the first half: however, an additional element here is a more leisurely, central section, effectively a slow movement, in which the material of the outer sections is infused with a dream-like haze. An unusual feature of the Romantic Fantasyis the unaccompanied harp solo, first heard near the start of the piece, which is exactly restated near the end of the work: context is everything here; though the two solos are precisely the same, because of the journey the listener has been on by the closing pages of the work, the second solo is perceived very differently.

The seven players of the Romantic Fantasymarked a deliberate move out of the familiar orbit, for me, of chamber music, towards orchestral writing – a major work for symphony orchestra normally being the final piece in a PhD porfolio. But in the meantime I received an unexpected commission from Manchester University’s resident string quartet, the excellent Quatour Danel, for a ten-minute composition. After three big single-movement works, I wanted to ring the changes with this, my second string quartet (which ended up as a 16-minute work): drawing on my study of cyclic processes for my Master of Arts degree, I hit upon the idea of writing a piece in which three strongly-related, yet distinct, movements depict different members of the same family: definite individuals, but unmistakably belonging to and resembling one another as well. Hence, my String Quartet No.2: Three Portraits (2011). This structure is, in a sense, a reworking of the ‘continual variation’ principle: the linking undercurrents between the movements are numerous, but largely covert rather than overt. The three movements are entitled Impulsive One, God-Seeker and Arguer, and the piece concludes with a conciliatory Epilogue, drawing together, as one might expect, different strands from the three preceding movements. The most radical passage of this composition is the opening, again Carter-inspired: I juxtapose passages of maximum density (all four players playing extremely fast and loud in dense dissonances) with passages of minimum density – that is, complete silence!

The String Quartet No.2 was the first piece I completed under my second PhD supervisor, Kevin Malone. Less confrontational than Phil Grange, Kevin helped build my confidence to get over the finishing-line with my studies, but was nonetheless willing to challenge whenever he sensed I was reverting to tired old tricks, or not digging deep to be the creative best that I could be. I owe Kevin a lot, and his kindness and generosity towards me is the more impressive given our radically divergent world-views.

I finally grasped the orchestral nettle in 2011-2013 with my thirteen-minute tone-poem, Mourning into Dancing. I originally conceived this piece as being an Introduction followed by four thematically-related sections – Lament, Processional, Scherzo and Finale – each new section being faster in tempo than its predecessors, aiming for a sense of accumulative impact and excitement as the piece progresses: however, in the act of composition, this plan appeared overly simplistic to me, and Finale actually begins at a somewhat slower tempo than the Scherzo. A sense of accumulative impact is achieved by quite subtle cyclic procedures, rather in the manner of my String Quartet No.2. For example, in the Introduction, the brass boldly proclaim a brief, four-note chorale: at the end of the Lament, this dissonant idea is transferred to the upper woodwind, losing its former bluster, and imbibed with mystery; in the Scherzo, the chorale is extended into a three-phrase theme, the strings moving in rich, contrary motion harmony, against rhythmic interjections in the trumpets and wind; near the start of the finale a ‘Cool Chorale’ appears, again three-phrases long, but quietly understated; and at the climax of the finale, it resurfaces as a ‘Corale Trionphale’, in context perceived as a natural culmination of the entire composition. Another unifying device in Mourning into Dancing is the use of a particular sonority – in this case, the timbre of the bassoon, to which is given all the recitative-like solos and duets which effect the transitions from one section of the work into the next. A further, rather unusual binding agent in Mourning into Dancing is a three-note rhythm – a short anacrusis, followed by two longer notes – introduced by the timpani in the first couple of bars, a rhythmic cell which permeates the entire composition.

A pleasing discovery for me in writing Mourning into Dancing was that I had an instinctive grasp of orchestral colour, though I had not written for full symphony orchestra since the orchestration exercises of my undergraduate days. A hugely helpful text for me in this regard was Lovelock’s book on orchestration: the simple message I gained from Lovelock – particularly with regard to the woodwind family – was, in a full orchestral texture, if you want an instrument to sound well, use it in its most powerful register. Child’s play, really, but a lesson I’ve never forgotten!

The final piece in my PhD portfolio was my Brass Odyssey, for Brass Band and Eight Percussionists. Towards the end of my years of postgraduate study, Manchester University was blessed with an outstanding brass band, and – continuing my resolve to write for unfamiliar instruments and ensembles – writing a substantial piece for the University Band seemed an obvious step to take. Brass Odysseyis twenty-three minutes long, and in two parts: Part I is entitled Elegy, and Part II (which follows Part I without a break), is entitled Towards Rejoicing. I must confess to an ambivalence towards brass bands! The particular challenge they present for a composer is that the brass instruments blend so beautifully, and make such a homogeneous sound, that after a few minutes’ listening (I stress, this is purely a personal opinion!), I get bored, and long for some grit and variety in the timbre and texture. My way around this in Brass Odyssey – like many another contemporary composer -was to employ a huge percussion section, and to vary the brass sound through copious use of a wide variety of mutes.

Lament and Processional were the first two sections of Mourning into Dancing, and the twin threads of grieving and of a funeral march are equally ubiquitous in Part One of Brass Odyssey. There is, it seems, a deep well of melancholy at the core of my personality, which finds spontaneous expression whenever I undertake to write genuinely slow music… Near the end of the Elegy, there is a brief, dazzling shaft of light in the form of a fleeting G flat major triad – the only major chord in the first twenty minutes of this piece – followed immediately by a catastrophic collapse.

From the shattered remnants of the Elegy, the music tentatively reaches out towards the optimism of Part II, Towards Rejoicing, which consists of four dance episodes book-ended by five appearances of a two-phrase, unison, Ritornello Theme: the transitions between the episodes also feature recitative-like solos for individual brass instruments, coloured by interjections from the percussion. My predilection for asymmetrical additive rhythms comes centre-stage in the dance episodes: a longing to avoid rhythmic squareness and predictability has shaped my music ever since my early twenties, and finds its most radical expression here. At Manchester University we had a Balinese-style gamelan ensemble, and I imitate the sound of a gamelan orchestra in an amusing passage (bar 614ff) where a jazzy main theme is played in a metrical canon by four different sections of the band – as I told the Tredegar Town Band in rehearsal prior to their recording, a clear example of counterpoint ‘gong wong’…

Final Period (2013-2026)

Finishing my PhD felt a considerable achievement – over six years of supposedly part-time study I put in many more hours work than for my undergraduate degree, and realistically achieved what I had set out to do back in 2007, in finding ways of creating large-scale instrumental structures in a contemporary Classical idiom. Being awarded my PhD was also something of a relief. There is definite pressure for anyone working towards submitting a PhD portfolio; we postgraduate composers are, supposedly, in the field of research, and therefore beholden to the powers that be to be quite definitely original, and to break new ground. True, in beginning every new composition, I always do try to set at least one unfamiliar stylistic parameter, to keep things fresh and avoid repeating myself: however, a self-conscious striving for originality can, I believe, militate against spontaneous, unfettered musical inspiration, and particularly against simplicity, sincerity, and directness of utterance. Significantly, therefore, my first piece following the award of my PhD was a Te Deum, for Choir, Vocal Soloists, Organ and Large Symphony Orchestra, a conscious celebration of the English Choral Tradition, incorporating echoes of Handel, Parry, Holst (‘Hymn of Jesus‘), and Walton (‘Beltshazzar’s Feast‘), but with some authentic Stevens in the mix, particularly in the more probing and mystical passages. This direct and approachable work falls within the performing capabilities of a good amateur choir and orchestra – in strong contrast to the six pieces in my PhD portfolio, which are all extremely taxing to play.

Completing the PhD in 2013 at the age of fifty-five marked the end of my Middle Period as a composer, and an obvious question then loomed: where did my music go from here? I did not have any sense of having written myself out, of creative burnout, but neither did toddling on in the same old way seem an option either. Over the year or so after the award of my PhD, three intertwining strands pulled my creative imagination onto the territory it has inhabited for most of the last decade of my life.

The first strand involved my main instrument, the cello. As I have observed above, writing short pieces, sometimes in haste, can be an excellent way of testing whether a new creative impulse can take flight, or not. And, in experimenting at the cello, I began writing and improvising melodic lines using the interval of a third of a tone. This is a classic case of the sheer physical nature of playing a particular instrument leading to a specific, unusual, compositional device. I am sure I am not the first composer in history regularly to employ intervals of a third of a tone, but, compared to quarter-tones, thirds of a tone are very unusual. Yet, to a cellist, these intervals lie comfortably under the fingers (whereas for viola players, and especially violinists, thirds of a tone are rather too close together to easily be played at speed, as are quarter-tones for cellists). I tend to use thirds of a tone in three ways: in rapid sequences, either ascending or descending, forming in effect a compressed chromatic scale; as auxiliary notes, which resolve onto conventional pitches, in the manner of appoggiaturas; and as held dissonances, or ‘stray’ pitches, operating somewhat as ‘blue’ notes do in Jazz, creating a deliberately strange, other-worldly effect. This microtonal development – which I did not see coming! – refreshed my lyrical voice as a composer, and open up new harmonic possibilities which I have not, as yet, fully explored.

In the years since 2016 I have written, and myself recorded, sixteen pieces for unaccompanied cello. In the majority of these pieces, the introspective side of my creative personality comes to the fore. A solo cello is excellent for the expression of emotional intimacy and depth, and arguably these pieces represent my most personal, private and individual music, shorn of flamboyance and display – soulfulness become sound, if you like. By no means all of these pieces are miniatures: Toward the Unknown Region and Unfailing Stream are both about seven minutes in length, and each, as their titles suggest, are small-scale tone-poems for the cello, uncompromising explorations of interior space, of the mystic aspects of mainstream Christian spirituality.

My experiments with microtones first became integrated within a major work in my single-movement Sonata Romantica for Cello and Piano(2019), which is just shy of half an hour long. The genesis of this piece is unusual. For our reflective Good Friday service at my home church in 2019, I was very generously given space within the service, to provide unaccompanied cello improvisations on three of Jesus’ seven last ‘words’ (or sayings) from the cross. I did genuinely improvise in the service itself, but in advance prepared a short, opening gesture to set each of the improvisations on its way. For the darkest of the seven ‘words’, ”My God, my God, why have You forsaken Me?” I hit upon the gesture of a plucked open A string, combined with the same pitch, bowed and tremolo on the D string: with the addition of a high piano tremolo, this became the start of Sonata Romantica. An unusual feature of this work is the relationship between the two instruments. As any cellist will tell you, the combination of piano and cello is problematic: the piano easily swamps the cello, especially when the cello is playing on the lower three strings (harpsichord and cello is a much more natural balance): one obvious solution to this difficulty is to alternate solo passages for each instrument, and this happens frequently in Sonata Romantica, giving the effect of a conversation, the two instruments giving their pianistic, or cellistic, ‘takes’ on essentially the same material. The alternating of solos comes to a head near the end of the work, where both players, in quick succession, are given substantial solo cadenzas, harking back to my Fantasy Sonata for violin and piano of thirty-five years earlier, where a violin cadenza is played near the conclusion of the first half of the piece, whilst a piano cadenza appears at the parallel point in the second half of the composition.

My second strand into compositional renewal – a common strand for many composers – involved the inspiration flowing from personal contact with some particularly outstanding instrumental players. I first heard the Amici Bassoon Trio at the Royal Northern College of Music in 2014, and was hugely impressed, both by the quality of their musicianship, and the rich expressive possibilities inherent in the rare combination of three bassoons. I sensed – and still do – that the bassoon is an instrument whose time has not yet come, and I quickly wrote three reasonably substantial works for the Amici: Five Portraits; the Sonata for Three Bassoons; and the Cinematic Fantasy. The bassoon is, in a sense, three instruments in one: reedy and penetrating in the lower register; mellifluously lyrical in the middle register; and intensely straining in the upper register. Over the next couple of years, on the back of my contact with the Amici (who were at this time regular performers at my annual charity concerts in Emmanuel Church, Didsbury, concerts which ran from 2006 to 2016), I wrote one of my most ambitious works, my Bassoon Concerto. In three movements, and lasting over thirty-five minutes, this composition pits the bassoon against a large and colourful orchestra, including in addition to the standard instruments, marimba, xylophone, vibraphone, drum-kit, harp, piccolo, alto flute, two cors anglais and a bass clarinet. The concerto is a tour de force, but always in terms of stretching the bassoon to its expressive limits, rather than indulging in virtuoso display. Having fully familiarised myself with the bassoon’s capabilities, this piece was my way of telling the world, ”Look, this is what a bassoon can do!”, and Adam Mackenzie’s wonderfully committed recording with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra gloriously reinforces the point.

The finale of the Bassoon Concerto marks the first appearance of a new structural device in my music. Whilst the structure of many of my large-scale compositions is founded upon adaptations of Classical Sonata Form, I was beginning to feel constrained by the emphasis in traditional Sonata Form upon unity and coherence – the sense that the second half of an extended movement was derived almost completely from the material already presented in the first half. I wanted the freedom for a movement to veer off in a totally unexpected direction and to catch the listener unawares. So, after a turbulent, climactic passage on full orchestra in the Bassoon Concerto finale, the texture clears, the volume level subsides, and the bassoon sings out a childlike, disarmingly simple Nursery Theme, which is immediately restated by the woodwind. Then, another twist, as orchestra and soloist launch headlong into a frantic, ‘Presto in Blue’ section, giving the standard twelve-bar blues a contemporary flavour by incorporating lop-sided additive rhythms. As a composer I have always set a high store on motivic development in music – Beethoven is, truthfully, integral to my creative DNA – but daring to spontaneously go out on a limb with new material towards the end of a movement, simply because my musical instincts tell me it should be so, has I hope widened the expressive range of my large-scale pieces.

I met David Jones, Head of Piano Accompaniment at the Royal Northern College of Music, when I joined his vocal group, Alteri, in 2015. David’s son, Alexander, is a fine double bassist, and in keeping with my penchant for writing for neglected, or ‘Cinderella’ instruments, I did not need much persuading to compose a set of Six Duets for Double Bass and Piano (2015). The ground-breaking piece within the set is Obsession, which, very unusually for me, is founded upon a four-note rhythm of a crotchet, a dotted crotchet, a quaver and a minim – or, if you prefer, note-lengths of two, three, one and four quavers, forming two bars in five-eight time. This rhythmic cell – or straight-jacket, to extend the prisoner metaphor – was a classic case, for me, of a rigid compositional parameter acting as a spur to my creative imagination: the fifty-eight unbroken repetitions of the rhythmic cell forced me to utilise a particularly large compositional bag of tricks (for example, the two instruments concurrently playing in different time-signatures, and the piano simultaneously playing legato in one hand and stacatissimo in the other, double-stopping col legno in the double bass, both players tapping their instruments, etc., etc.) to sustain interest, and as a result I believe Obsession is one of my most successful and original shorter pieces.

Another player to inspire me as my Late Period got into full sway was the recorder player, John Turner. John knows everyone who is anyone in Classical music, in the north of England especially, and he commissioned me to write a piece for recorder and chamber orchestra in which each movement would depict a character in the British Royal Family. The result was a five-movement composition, Balmoral Suite, written in pastiche Scottish folk style – an idiom that comes very easily to me: it remains perhaps my most popular piece, and I am hopeful that its relaxed tunefulness might yet propel it towards the top of the Classic FM charts! Using a family relationship to bind together different movements of a composition recalls my String Quartet No.2 (‘Three Portraits‘), and also the Five Portraits for bassoon trio. Writing approachable Light Music is an important secondary thread running through my output, and my decades of experience in church music as both composer and player give me, I trust, a sense of the type of melodic music that the average music-lover can most naturally – and enjoyably – relate to.

Composing my Bassoon Concerto came to me surprisingly easily, considering my relative lack of experience in orchestral writing: the theatrical and declamatory aspects of composing a solo concerto suit the extrovert, dramatic (some would say melodramatic…) side of my nature, and writing a concerto lacks the cultural baggage associated with composing a symphony. Thus, following the Bassoon Concerto, two more very substantial concertos came into being, for Cello (2020-2022) and for Viola (2022-2023). Whereas the Bassoon Concerto was a three-movement work, each movement being approximately twelve minutes long, both the Cello Concerto and the Viola Concerto are four-movement compositions, each with a very short scherzo placed second. Unsurprisingly, microtone inflections abound in the Cello Concerto, subtly colouring the extended lyrical lines with which the solo cello part abounds. After a Neo-Classical first movement dominated by the interval of a major second, complex polymetres give the scherzo a strange, other-worldly ambiance. The slow movement again uses my favourite structural device of Statement – Varied Counter-Statement, where the second half of the movement is not so much a decorous variation of the first half, but rather a fulfilment and realisation of its expressive potentialities. The finale energetically attempts to shrug off the introspection of the Adagio, and as the pace increases, the orchestra builds to a climax, with the major seconds of the opening movement again to the fore. Then follows an impetuous cadenza for the soloist. I fully intended my Cello Concerto to end, following the famous examples of the cello concertos by Dvorak and Elgar, with a slow, heart-rending coda. However… when it came to it, the music simply didn’t want to go there, so – to my considerable surprise – the Cello Concerto concludes with a light-hearted coda which speeds up (and metrically transforms) the main finale theme, provides whispered reminders of the opening of the whole work, and playfully returns to the home key of D, as if to ask, ”What was that past half-hour of angst all about, then?”

My Viola Concerto bears a superficial resemblance to the Cello Concerto: both works share a four-movement design, and both are expansive, serious compositions, lasting well over thirty minutes. But there the similarities end. The Viola Concerto begins with a ‘motto’ theme, intoned by the solo viola, which reappears several times throughout the work (harking back, in this respect, to my Sonata for Unaccompanied Cello, from 1987). A distinctive feature of the opening movement is the way certain passages are centred, both melodically and harmonically, on a particular interval – in the first instance a major sixth (bar 71), and in the second instance, a major third (bar 102). Creating a distinct identity to either a particular passage, or a complete shorter composition, through restricting the number of intervals at my disposal, is a characteristic Stevens fingerprint – see, for example, the first of my Three Bagatelles (2004),for solo piano (limited to perfect fourths and semitones), or Dona Nobis Pacem (1994) for two French horns and chamber orchestra (limited to perfect fourths and fifths, moving in contrary motion). This technique has served me well across the decades, but with a proviso: I always need to give myself the flexibility and freedom to break my self-imposed harmonic restrictions when the expressive imperative demands it, otherwise I am enslaved by my compositional processes, or, to put it another way, the tail starts wagging the dog!

The structure of the first movement of the Viola Concerto is a characteristic adaptation of Sonata Form, until, towards the end of the movement, there is a sudden shift in direction with the introduction of a completely new theme, an ostinato melody first played on solo viola, and building to an immense climax as it spreads through the whole orchestra. Then, another example of me ‘stealing’ a procedure from an earlier composer: as a seventeen-year-old student, I performed Shostacovich’s Cello Sonata with a fellow-student, and in the parallel stage of that composition’s first movement, Shostacovich recalls his opening theme, but at a much slower tempo than before, giving the coda to the movement a tragic intensity all the preceding music in that movement had lacked. I copy the Russian master, and, in instructing the soloist to play senza espressione, paradoxically, the opening theme is rendered more expressive, for being played in a dead-pan way.

The ensuing scherzo is brief and rapid – a necessary foil to the slow conclusion to the first movement, and the unhurried pulse of the slow movement, which opens by recalling the ‘motto’ theme. Structurally, this movement shares the Statement – Varied Counter-Statement pattern of the Adagio of the Cello Concerto, but the full-blooded climax of the movement is given to the orchestra alone, brass loudly declaiming a harmonic progression taken from the opening bars of the composition. The finale is brimming with energy, but eventually this burns itself out, and there follows a reflective cadenza for the soloist – thoughtfully musing over many earlier ideas – then a heart-felt coda, in which the melodic strands running through the entire concerto are poignantly woven together: undeniably the crux of the piece. The concerto draws towards a sober conclusion, but beyond, or even amidst, the undeniable sense of grief, a surprising peace is uncovered in the very final bars, as the ‘motto’ makes a last appearance, pizzicato, on solo viola.

The third revitalising strand in my music in my later years is down to my late mother. Gillian, who died in 2020, three months short of her ninetieth birthday, was a keen supporter of my music, and towards the end of her life said to me, several times, ”Don’t wait ’till I’m gone: if you need money now in order to do important things, just ask!”. In 2017, on the death of Gillian’s third husband, the engineer, Victor Bryant, we became aware that I could prematurely inherit a considerable amount of money from my mother, free of inheritance tax, by a ‘deed of variation’ on her will; and, thanks to my mother’s generosity and initiative, this indeed came to pass. There were two immediate consequences: I could now afford to stop home tutoring (after ten mostly enjoyable years, my enthusiasm had finally petered out), and devote myself entirely to composing; and I was now in the very privileged position of being able to pay top musicians professional rates to record my most important pieces.

I set about recording my major works with a sense of urgency, an urgency that later developments in my health events were to show was not misplaced. Recording one’s own music, and all the practicalities around producing CDs, is a demanding activity, requiring steely determination and bagfuls of perseverance! A particular, perhaps surprising pitfall in this process is that so many professional musicians are simply hopeless at administration, organisation and verbal communication: setting up recording sessions is therefore stress-inducing, to put it mildly!

Some composers have a very ”hands off” approach to recordings, being content simply to let the players get on with it: I must admit that I find this mindset strange, bordering on crazy! In general, the world will judge the worth or otherwise of a contemporary composer’s music on the basis of the quality of their recordings – except in the very rare instances where a contemporary piece because a standard repertoire work. Therefore I regard it as absolutely vital that I am present to oversee my recordings: it’s not that professional players won’t perform with a reasonable degree of accuracy and polish – they will – but however meticulously one marks one’s scores and endeavours to make one’s intentions clear, the elusive right ‘feel’ of a composition can easily be missed by even the best and most sensitive of players: at such times, a single sentence from the composer may be all that is required to set things back on track, but if the composer is absent, that cannot happen. And if the musical world regards me as a control freak, I can live with that!

I find that the prospect of an upcoming recording clarifies my mind wonderfully in terms of judging whether a particular piece, from a purely compositional angle, is yet in optimum shape or not. Received wisdom is that one should avoid revising pieces from decades earlier, since almost inevitably one’s compositional style has moved on in the interim, and one is now trying to say rather different things through one’s music: to tinker might mean to create a mish-mash of two incompatible musical idioms, and do more harm than good. Undoubtedly there is some validity in this perspective. However, in revisiting a piece after several years, I find it much easier to be objective about its weaknesses – time gives the emotional distance conducive to honest self-assessment – and, in the interim, my skill-set as a composer has hopefully grown and strengthened, giving me, God-willing, an ability to solve compositional dilemmas that previously had defeated me. In returning to a piece, if I don’t consider it worth recording, it’s time to delete it from my catalogue of works: if I conclude it is salvageable, and a potential recording is imminent, my motivation for getting the composition ”just so” is sky high. Leaving to posterity a second-rate recording of a second-rate piece would be humiliating indeed!

Linked to the topic of revisions is that of arrangements: not of other composers’ music (I don’t do this, unless one counts my variations on popular tunes such as Bobby Shafto and Auld Lang Syne) but rather the creation of different versions of my own pieces – usually duets involving a melodic instrument and a piano. If the melodic instrument is changed, the character of the original composition is subtly transformed, since (in any arrangement worth its salt) the sonic capabilities of the new instrument need sensitively to be taken into account. This is a process I thoroughly enjoy! Apart from the obvious point that arranging an existing piece is much less hard work than writing a new one from scratch, the arrangement process causes me to think carefully about the essential nature of the new instrument, and, where necessary, to make quite radical changes to the original piece. For example, when I came to arrange my Concert Rondo (2016), originallyfor treble recorder and piano, for oboe and piano, a literal transcription of the recorder part onto the oboe would have been virtually unplayable: the recorder excels in fast, light, passage-work, which is much more physically demanding to play on the oboe; thus, for four-bars, an unbroken, virtuoso sequence of semiquavers is transferred from the oboe to the piano, giving the oboist (and the listener!) a moment of repose. Additionally, the treble recorder’s lowest note is the F a fourth above middle C, and it is weak in its lowest register, so when playing in this range the accompanying piano texture is necessarily spare (or the recorder cannot be heard at all), whereas the oboe’s range reaches to the B flat just below middle C, and – in total contrast to the recorder – this is its most powerful register (indeed, it cannot play quietly on its lowest notes at all), so considerable re-writing was necessary (for both oboe and piano) for all the low-lying recorder passages in this piece. This type of arrangement has been well-described as putting on a new set of clothes: one’s core personality is unaltered, but new clothes change others’ perception of who we are, and can also give us the confidence to express previously concealed aspects of our true selves…

The Viola Concerto, finished in 2023, proved to be my last major composition. A few weeks after completing that piece, a colonoscopy revealed that I had cancer of the colon, and in June that year I underwent a ten-hour operation. Things looked hopeful for about twelve months, but a CT scan showed that the cancer had spread to my aortal artery, and that, medically speaking, any treatment would be purely palliative. Thankfully, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra made themselves available for six days in the summer of 2025 to record all my orchestral music, and additionally the Tredegar Town Band recorded a CD of my most important brass compositions in June and July: the summer months of 2025 have been action-packed indeed, and a final twist came with the RSNO generously agreeing to an extra studio session in August that year to record my last composition, the orchestral tone-poem, Into the Deep, completed in the spring of 2025.

Into the Deep lasts for sixteen minutes. It is predominantly slow-paced and, as the title suggests, probing and exploratory in character. More than in any other of my major works, sonority and tone-colour are central to the musical discourse: bitonal passages, where the music simultaneously inhabits two different tonal centres, abound, and the expressive dichotomy inherent in such passages is emphasised by assigning different dynamic levels and instrumental timbres to the conflicting tonalities – a technique strikingly employed, for example, at the very start of the work.

Taking its cue from my three solo concertos, for bassoon, cello and viola, Into the Deepmakes extensive use of both solo recitatives and extended lyrical solos for individual instruments which are not normally the centre of attention: so bassoon, contra-bassoon, bass clarinet, double-bass, tuba, and the three trombones are all, briefly, centre-stage during the course of the piece, often being heard at the upper or lower extremes of their register. Another colourist effect, unique in my orchestral music, is the use of the piano.

The title, Into the Deep, is a contraction of Jesus’ words to His disciples in Luke’s gospel, chapter five. The disciples have been fishing all night, and have caught nothing. Christ then tells them to ”Launch out into the deep”, and immediately their fishing boat starts to sink under the weight of a huge catch of fish. I love these words for their call to adventure and exploration: to eschew a risk-averse lifestyle, and instead to embrace life in all its fullness, with all the uncertainty and unpredictability that courageous living entails. I hope that, at my best, my music and my life have managed to embody that venturesome spirit.